In this text for the St Andrews Centre for Contemporary Art website, the Barbadian artist, writer and educator Annalee Davis reflects on her work A Hymn to the Banished (2022), made at the Dundee Contemporary Arts Print Studio as part of her project Contesting Landscapes of Distraction for the National Trust for Scotland’s Facing Our Past initiative, which addresses links between NTS properties and British-empire era enslavement. Annalee has written a series of posts for the NTS website exploring the genesis of the work, its development at Balmacara Estate in the Highlands, and the creation of A Hymn to the Banished. The St Andrews Centre for Contemporary Art was delighted to co-host a talk by Annalee in September 2022 with Dundee Contemporary Arts, during which A Hymn to the Banished was on display; here, Annalee reflects at longer length on the experience of developing the print edition and the research that has fed into it.

*

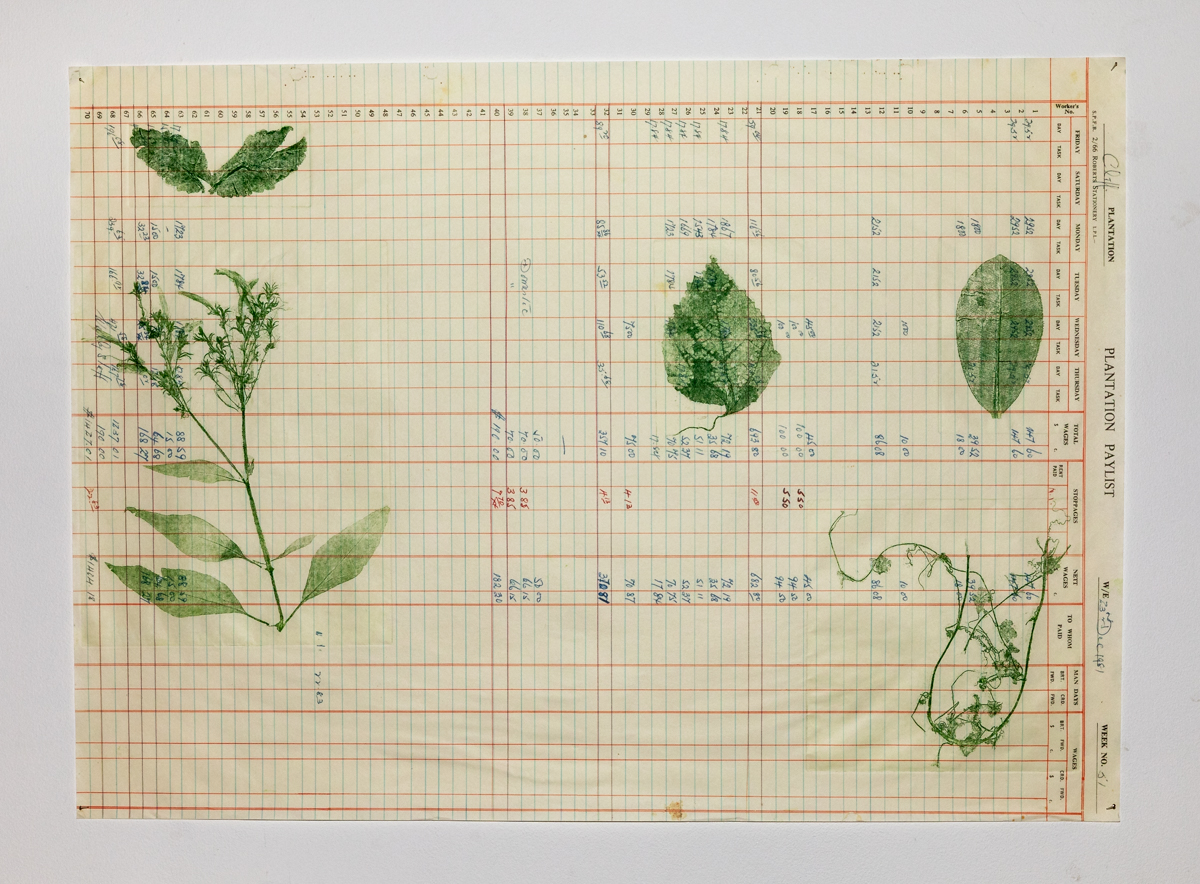

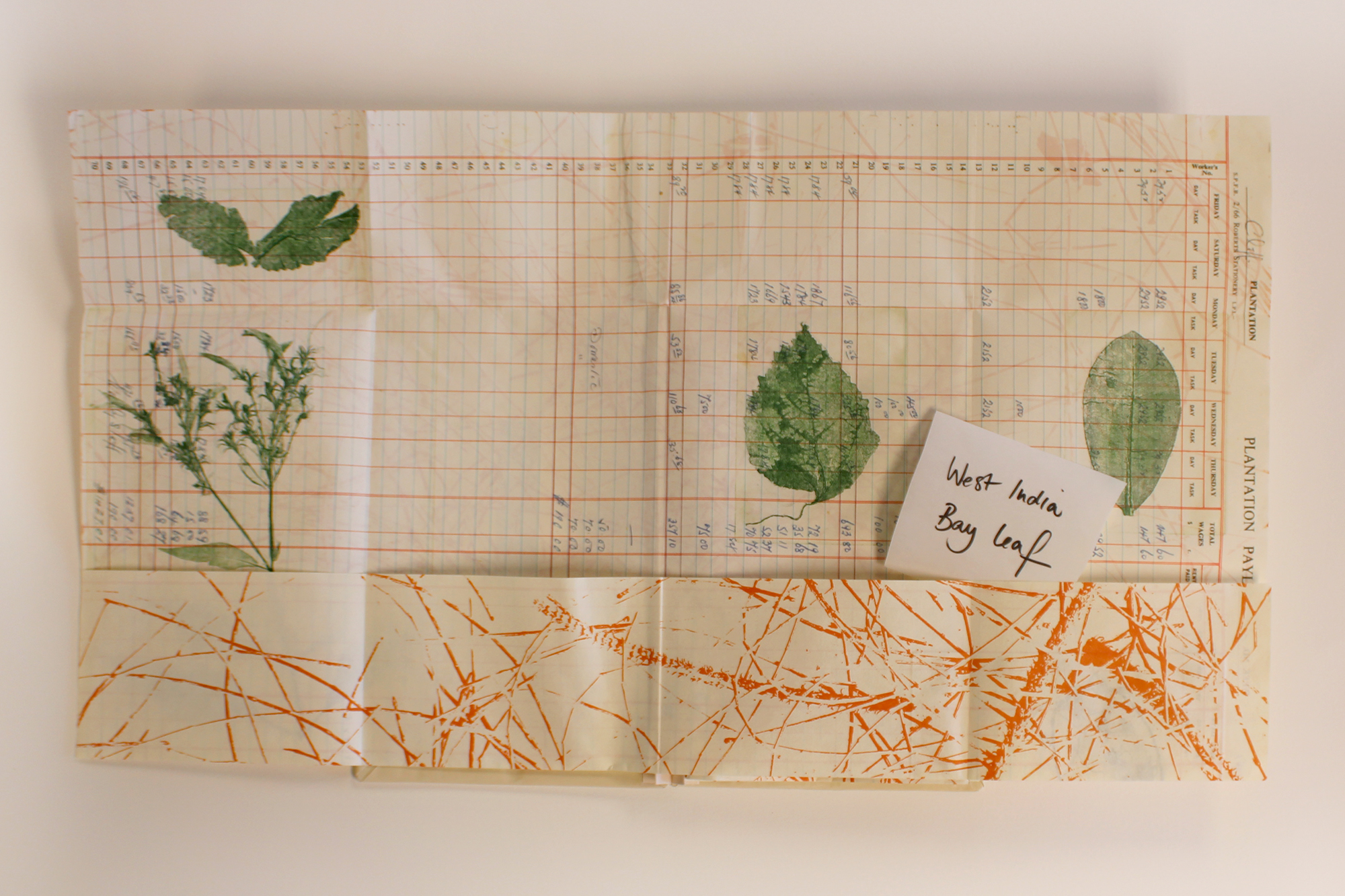

Francis Humberston McKenzie, Lord Seaforth, governor of Barbados from 1800–1806 and one-time owner of National Trust for Scotland’s Balmacara estate introduced many West Indian plant species to Britain’s botanical gardens. My own thinking about plants reconsiders their value in the expansion of the British Empire and sugar plantations as defining instruments shaping the West Indies, modernising Europe, and their role in the plantionocene. Additionally, as part of Scotland’s colonial ventures, McKenzie contributed to the evolution of living laboratories such as Kew Gardens among other botanical repositories that harvested West Indian plant material for research. I am intrigued by the subversive role of botany in resisting the colonial project’s oppressive regimes – whether in the Highlands or the Caribbean. Altogether, this meant that Balmacara was an appropriate location for my research to kick off.

Enough has been written about Seaforth and his ilk and his well-documented life as Barbados’ governor and owner of plantations and enslaved African people in Guyana. While the archives attest extensively to his life they are deficient in other ways. I focused on those left in the wake of the plantation, and the comparatively less well-documented tactics of refusal and survival employed by the dispossessed and marginalised.

In casual conversations with Scottish people, there was seemingly little awareness of connections between their country and mine reaching back to the early seventeenth century. This unknowing is understandable given there is no recognised Scottish expert working on 17th-century Scottish presence in the West Indies, a void further underpinned by a British history curriculum paying scant attention to this area of study.

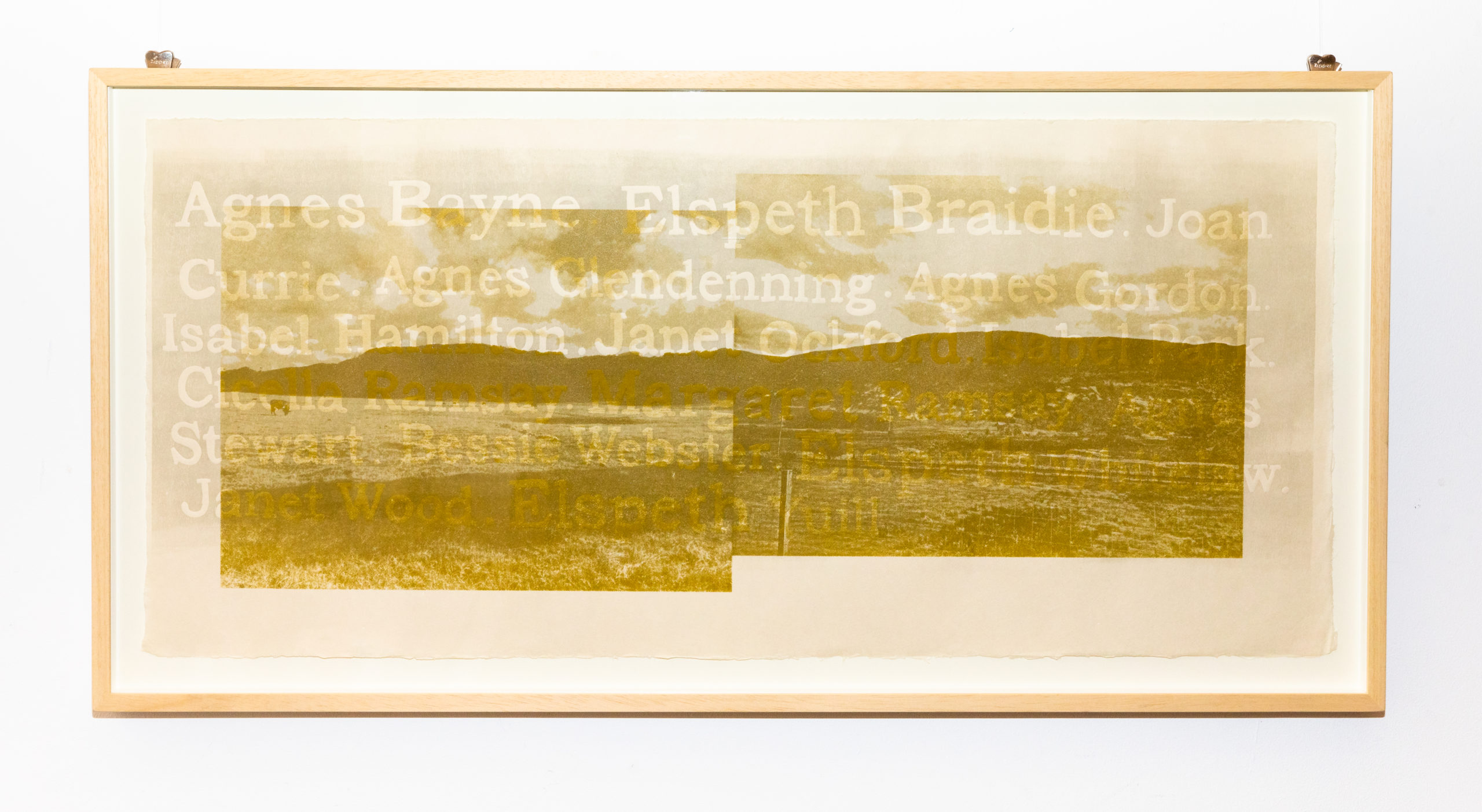

One useful publication by retired University of St Andrews history professor Dr David Dobson listed thousands of Cromwell’s prisoners who were exiled to the colonies in the Americas, including Barbados, and after battles in Preston (1648), Dunbar (1650) and Worcester (1651). Once again after the Covenanter Risings, he writes that hundreds more were transported to plantations, again including Barbados, some arriving as indentured servants. Others came as tradesmen, planters, doctors, and colonial administrators. Of the almost 2,500 who came to Barbados, only 152 were women and it was their deeply buried stories, specifically the fifteen female prisoners from the Edinburgh Correction House, that I became interested in.

Closer research aided my understanding of the role of Gaelic plant traditions across the Highlands – similar to those found in enslaved Barbadian society – such as the use of incantations and charms. Spirit-based rituals and healing methods survived forced migrations and carried systems of knowledge crucial for both endurance and defiance. Did these distinct Scottish and West African philosophies rub up against each other in Barbados and might the indentured and enslaved people have shared their botanic heritage with one another, becoming allied healers across divisions of language, nationhood, and race?

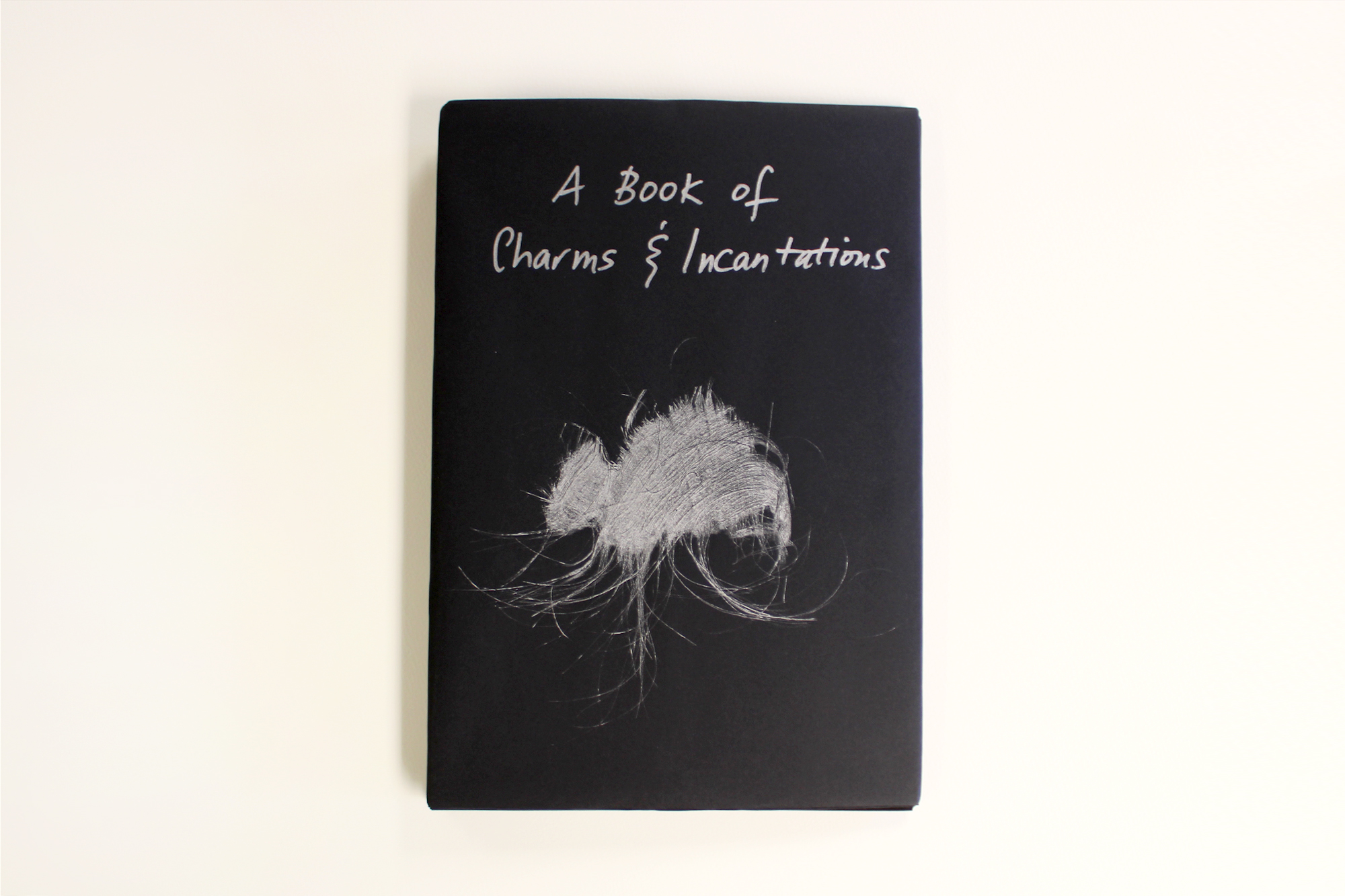

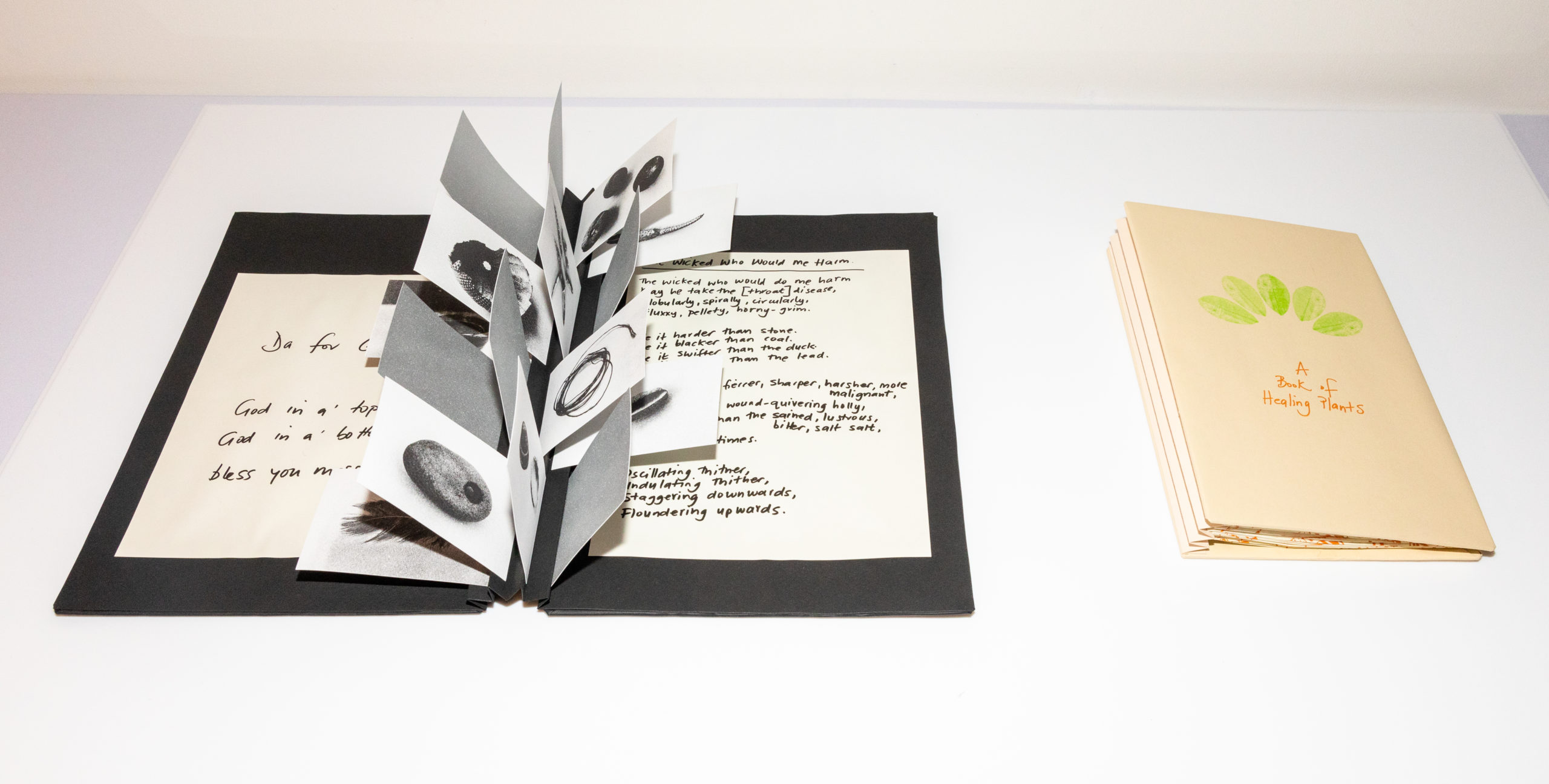

While the Scots have incantations transcribed in Gaelic and English, British colonial powers made African-derived rituals in Barbados illegal. The “spirit thieves” – as Erna Brodber referred to British colonial powers – deprived the Anglophone Caribbean of the written recordings of Obeah practices which were necessarily transmitted orally since practitioners were punishable by imprisonment, torture, or death. Obeah remained unlawful in Barbados until the late 20th century. However, two Barbadian incantations were brought to my attention by Dr Deryck Murray and made their way into my Book of Charms & Incantations. Recorded in the 1789 Letters on Slavery publication by William Dickson – a secretary to the governor of Barbados – it offers accounts of the virtues and abilities of the enslaved African people.

My piece, A Hymn to the Banished was made in collaboration with the printmakers at Dundee Contemporary Arts. This limited edition of three bespoke fabric-covered boxes lined with a screen-printed fishnet unfolds through a set of works comprising two handmade books, an impossible map, a scroll of banished women, a choker, wriggling parasites, and drift bean charms.

Collectively, these seven objects imagine the smaller moments in people’s lives impacted by the wide-reaching ramifications of the British empire. Informed by Scotland’s internal colonization – a rehearsal for the treatment of indentured and enslaved labour in the Caribbean – and their people’s struggles to continually adapt to the most inhumane of conditions, I became absorbed in understanding how land, oceans, and rituals sustained the evicted and stolen human beings. How did chants and incantations support people through the terrors of dislocation, offering a balm to their weary or diseased bodies? Did these uprooted people ever experience a sense of dùthchas or belonging in their new and foreign worlds?

Known as airne Moire (Mary’s beans) in the Outer Hebrides, and as drift seeds in Barbados, the nicker nuts or sea beans that float on the world’s ocean currents were used by Gaelic midwives for labouring women and in Barbadian enslaved African traditions. It may be that they offered comfort as amulets, held while repeating phrases to release the healing potential of plants, to bless homes, cattle, and sheep, or to ward off evil.

The Cuban essayist, Antonio Benítez-Rojo, addresses Caribbean culture in his book The Repeating Island, describing the region resembling a long annelid parasite moving through the bowels of the archipelago, revealing the plantation’s extractive nature. The screenprint and chine-collé image of wriggling hook, thread, whip, and roundworms allude to histories of expropriation as well as diseases that newcomers to the island would have encountered. Given the nascent stage of medicine at the time, treating illnesses with what was available would have involved using plants and charms.

The Scroll of Banished Women identifies fifteen women exiled to Barbados from the Edinburgh Correction house. Margaret Ramsay was one prisoner whose crime was not having a woman accompany her while she gave birth to a dead child, an offense for which she was whipped in the city’s streets and deported. Records tell us that others were exiled for interrupting a church service or not having a Book of Psalms in their home.

Remnants of the British Empire and its attendant unjust schemes of colonisation remain evident today with millions of people around the world impacted by its vestiges such as unequal access to resources, degradation of lands, eradication of biodiversity, displacement of people and the modification of ways of communal living.

Still faced with archaic models, some nation-states enact policies to create ‘morally acceptable’ environments. Thus we can draw a thread to some of today’s turmoils from similarly oppressive ideologies that once informed Edinburgh’s extradition of so-called immoral women to 17th-century colonial enclaves, or wealthy landowners’ desires to ‘improve’ lands in the 18th century by clearing thousands of rural folk replacing them with sheep to increase private wealth. 20th-century offshore detention centres in Australia, the UK’s Rwanda asylum plan and for-profit, privately run detention centres in the USA and Italy, the ongoing forced detention and ‘re-education’ of Uighur and other Muslim minorities, the ‘morality police’ in Iran or the Government Industrial School right here in Barbados governed by outmoded colonial legislation almost one hundred years old failing our young, poor girls and boys, are only a few examples.

A Hymn to the Banished is a secular prayer in the form of a visual meditation recognising the intuition, knowledge, customs and tenacity of our forebears and their capacity to confront and survive cruel, brutal conditions. The goal of shaping a more sustainable, empathic world requires that human and non-human kin are not seen as invasive species but rather as guests whom we might welcome, break bread with, and learn from. Human beings, like the soil, need to be nurtured to flourish.

Thanks to everyone in Scotland who has been so generous, welcoming, and supportive of this project. I appreciate the entire amazing team at DCA including Beth Bate, Sandra De Rycker, Annis Fitzhugh, Scott Hudson, Marriane Livingstone, Claire McVinnie, and Katie O’Mahoney. Thanks to the invigilators of my solo exhibition at the Steadings Gallery, Caitlin and Ciara Turnbull and Robyn Sands. It was a pleasure to speak about this new work in the five-city lecture tour including the first co-hosted by DCA and the University of St Andrews, at Plockton High School supported by the history teacher Colette Grant, with the knowledgeable Iain McKinnon at Skye Bridge Studios, serving (bush) tea to Christine Borland at Deveron Art Projects, and engaging with Emma Nicolson, Claire Ratinon, Shiraz Bayjoo, and Keg DeSouza as part of the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh and NTS panel at Edinburgh Climate Change Institute. And of course, exceptional gratitude to Claire Hammond, Hannah Lee, Jennifer Melville, and Iain Turnbull of the National Trust for Scotland for supporting this project from beginning to end and for being so wonderful to work with!

– Annalee Davis, 14 December 2022

For anyone interested in acquiring a limited edition of A Hymn to the Banished, please contact DCA Editions Manager Sandra De Rycker at DCA via email at [email protected]